|

Klara Filippovna Vlasova was born in Moscow. She was 10 when she went to study in the art studio at the Central House of Children's

Artistic Development. When she was 11 she was awarded the First Prize at the First All-Union Children's Drawing Competition.

In 1939 Klara continued with her art studies in the newly organised Art School in Moscow.

In 1941 together with the school Klara was evacuated to the village Voskresenskoe in Bashkiria.

Vlasova returned to Moscow in 1943 and shortly completed her studies. In 1944 she got accepted into the Surikov Moscow State

Institute without exams. She studied there in the art class of the renowned master S.V. Gerasimov.

Vlasova participated in the summer exhibition of student works in 1945. Her painting "Symphonic Orchestra" was highly

received by the critics who noted it as a work of an already accomplished artist.

Vlasova graduated from the Surikov Institute in 1950 and was invited to work on the mural for the pavilion

"Tajikistan" on the All-Union Exhibition VDNKh. The young artist went to travel around Tajikistan to make sketches

of her impressions of the country. Middle Asia became her favourite theme and a source of inspiration since that trip.

Dagestan was one of the other special places for the artist. Vlasova came across a house in a village Choh in Dagestan

that was built in the beginning of the 20th century and decorated by a local artist. She would come here every summer

to stay in the house and work. A very successful personal exhibition of Vlasova's works was held in Dagestan in 2012.

Klara Vlasova has been awarded the title of the "National Artist of Dagestan."

Vlasova had a "travelling" personal exhibition of her works "Roads and Directions". It was held in several cities

of the Volga Region - Samara, Saratov and Nizhny Novgorod. Apart from genre painting, Vlasova's works include a lot of still lives,

landscapes and cityscapes. She always thought of herself as belonging to the Moscow Art School. Her unexpected compositional

approach, colour combination and a genuine interest in the world form a very rich language. Vlasova's artistic vision

gradually reveals itself through each painting. She very finely recreates the moods of the nature as well as the dynamics

of the city. All her works are contemporaries of their time and are like an echo from the past.

Klara Vlasova's artworks are represented in the collections of the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, in the Museum of

History and Reconstruction of Moscow, in the Museum of Leo Tolstoy in Moscow, in museums of Vladimir, Makhachkala, Sochi,

Derbent, as well as private collections in Russia, UK, Germany, France, USA and Japan.

With a relentless desire to advance her professional skills, Anastasia has studied at the “Horizon” Artistic school in Moscow and is working toward obtaining a certification in Painting. She is a proud Founding President of the Art History Club at the Schule Schloss Salem School.

“I was born in Moscow, Russia in 2005 where I attended the International School of Moscow and the Lomonovskaya School of Moscow. In the fifth grade, I transferred to the Cambridge International School where I studied until 2018. Finally, I moved to Schule Schloss Salem, a boarding school in Germany, where I’m currently in the eleventh grade in the International Baccalaureate program.

I discovered my passion for the arts from a young age. While I started off drawing princesses or fairies, I eventually moved to drawing professional pencil sketches or landscapes painted with oil. I like detailed drawings, to highlight every element of our surroundings: place, view, location, building, vase, person and animals. I have over 100 art pieces in my collection.

At the age of 11 I dived into the arts more deeply. I attended an arts school where I drew still-life drawings and improved my painting skills, such as brush techniques and knowledge of colour theory. I was attracted to drawing with paints and oil as they had a wide range of colours and rich colour depth, so it seemed more creative to me. Once I transferred to a boarding school, I attended an Arts club in years 9 and 10, where I enhanced my pencil sketching skills. Now I am an organiser and a leader of the Arts History club where I analyse paintings, learn about artists and teach students that have the same passions and interests that I do.

Now, my goal is to major in Architecture and learn appropriate skills to pursue Historic Preservation. Historic Preservation shows us the historic value that architecture can hold and how delicate we should be with art. It emphasises the importance of history and historic art, and it can teach us what mistakes not to repeat and which achievements we should be proud of. To me architecture is not just art. It holds and embraces my biggest ambitions.”

Irina Danilevskaya was born in Moscow on September 30, 1980. She started drawing very early and followed her passion all her life.

The family lived on Sretenka Street in Moscow. Irina’s father was entomologist, for his work he undertook many trips to Asia. He often took his daughter with him. Irina painted a lot during these Asian expeditions and brought home landscapes, which were becoming more and more refined.

When Irina was 16, she went to Paris with her father. She attended design courses at the Sorbonne for several months. In 1996-1998, she lived and worked in Berlin, then studied at the Moscow Academic Art College, with the teacher Ilya Pravdin having played a major role in her formation as an artist.

Soon after graduation, Irina, who had been constantly perfecting her skills, realized that most likely she will have to work “for the desk drawer”, with no appreciation and/or any demand for her artwork.

This realization, however, not only did not hinder or prevent her from painting. On the contrary, it gave her immense power and allowed her to escape from material ambitions and do what she herself wanted to do most - to paint, aiming to achieve the highest level in her art and technique.

Many times she had to live from hand to mouth, especially, after her daughter Marta was born in 2004. Her relentless art perfection and focus reaped the result - she was noticed, offers began to arrive to sell her artwork under a false name, to paint by request. Only one case is known when she gave in to these requests and painted a portrait.

Things started to improve in 2007. Irina went to Paris, and then spent 2008 in New York and San Francisco. She returned home with a suitcase full of paintings, studies and material for new series of work, all inspired by the New York architecture and the literature works of the writer Isaac Bashevis Singer.

Literature provided enormous influence on her work: Evelyn Waugh, Brodsky, Savinkov, and Babel. Irina read a lot and knew many poems by heart. She relived them in her artwork, reworking her emotions from one series of works to another. Irina possessed an exceptional memory, she knew by heart the poetry she had ever read, which, later, when mortally ill, amazed doctors - she reacted to pain by declaring through her teeth the poems by Slutsky, Brodsky, Tsvetaeva.

In 2011, Irina spent a month in Havana, which was followed by amazing Cuban cityscape series.

In 2013, at the age of 33, after several unsuccessful operations, doctors pronounced a verdict: sarcoma - one month left to live. Nevertheless, Irina was able to live for another year and a half. During this short time she had her only lifetime exhibition in the A3 gallery and painted about a hundred more works, the last of which she started to paint at the First Moscow Hospice a week before her death. The painter is no longer with us since April 28, 2015. She left the world her daughter Marta and an amazing array of paintings.

Irina's artworks are very different. It is difficult to choose from them. Irina wrote in series, repeating, reworking one motive many times. It is not a hard-set code, but rather an infinite number of combinations, with varying meanings and intonations.

It is hard to say, which one of her paintings is better, it is rather which one speaks to you. Danilevskaya as a painter is “heir to all her relatives.” Relatives, as is often the case in Russian art, are French painters.

'French sound in her paintings recalls different representatives of the Paris School, each viewer sees “a little more” of Bonnard, Monet, Cezanne, Van Gogh or Matisse, depending on his own preferences,” - wrote the art critic Valentin Dyakonov about Irina’s works. Irina does not imitate French Art, she uses the styles of her predecessors to create her own language. In the series 'Stockings' French lightness gives way to the Viennese Secession. Looking at girls in stockings one is reminded of painful broken nudes by Egon Schiele.

The combination of pain, rudeness, fragility and beauty is very close to Irina. There is a feeling of a rebirth process that is happening right before our eyes, mesmerizing us, setting the work of Danilevskaya apart from her predecessors. Looking at her still lifes we realize that their beauty is not the beauty of the subject and not even the beauty of a painting. We are witnessing the moment of transformation of the object. It eludes us, becoming a brushstroke, a fragment of space, carrying us along.

There are works that are more literary. Buffet (2001), Palms (2002), Blue Evening (2006) are not united by the artist into a series, but the feeling of kinship of the depicted does not leave us, as well as the world in which they are. This world is radiant and painful at the same time. All characters are fenced off from us. They are immersed in a slow doze. The narrow format of horizontal and vertical stripes enhances the casual peeping effect. We see everything as through the strips of blinds.

We do not see everything, inventing or guessing a lot, whether it is a home interior or exotic Cuba. But the more we look, the more we are attracted to this world that does not let us into itself.

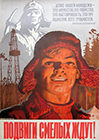

We decided to devote this exhibition to labor, a deeply important and beloved topic in the Soviet Fine Art.

The name of the exhibition is a slogan from the poster made by Victor Ivanov in 1964. This title carries one of the most important messages of the Soviet art of the 1920s to 1970s.

Labor was often portrayed as the ultimate exertion of forces, as ecstasy, sometimes as an individual action, but more often as a collective organised effort.

|

There is a young man of the 1960s, full of strength and smiling in the foreground of the poster. In the background we see the image of an ascetic Red Army soldier

in budenovka who has replaced his rifle with a pickaxe. The metaphor is obvious - an eternal battle, effort, overcoming - that is what awaits him in the future.

|

|

The same reminiscence of 1920s, and the combination of war and labor motives into a single process we can see in the work by Ivan Shibnev "Construction of the Railway" from 1947.

The central figure is the Red Army soldier in Budenovka with the quote from the famous "Defense of Petrograd" by Alexander Deineka turn the scene of labor into a battle scene.

|

|

The painting by Karl and Zinaida Tanpetr "Construction of the Kupsayskaya Hydroelectric Station" from 1961 shows another interesting interpretation.

The composition of the painting is built on the contrast of the majestic Kirghizian mountains and the barely noticeable construction equipment somewhere far below.

Amid this contrast, a huge dam seems to be part of the natural world. It seems that the dam cannot have been built by these small machines.

People are practically invisible, only one pair is depicted, away from the dam and from the main works, and they rather dissolve in the landscape rather than form it.

|

|

Another important aspect of the topic is the demonstration of labor achievements to the international community.

The masterpiece here is the "Visit of a Foreign Delegation to the Communist Labor Brigade of V.I. Lenin Plant."

This is a full size study for a monumental mosaic made in oil on canvas. The absolute conventionality of the technique - involuntarily pointillism, painting that

imitates small pieces of mosaics with colored strokes turns this traditionally socialist plot into an absolutely modernist work.

|

It is these internal discrepancies between the language and the plot, and unexpected additional meanings and metaphors that bring a particular interest to these works.

NB Gallery shows the paintings by Klim Chursin which have been just shown at the personal exhibition of the painter

at the major museum of the Russian South - the Krasnodar Fine Art Museum.

How did the painters in Soviet times travel? Where would they go and what beautiful and remote places would they depict?

The diversity and vastness of Russia - Kamchatka (open to the Foreigners only since 1991), Asia, the North,

the South - is revealed through the eyes of the artist.

The artist's son, artist Yuri Chursin remembers: "There are people whose work lights them up". Klim

Nikiforovich Chursin was one of those people. Painting was his life. There seemed to be no place that he did not

capture in his landscapes in the entire Soviet Union, from Kamchatka to the Baltics. Every time when he visited a

new place, his eyes would see the beauty sometimes not noticed by the locals. Klim Nikiforovich made field

easels and boards for his trips himself. All his works were painted en plein air.

Chursin experimented in finding

the most expressive technique possible. He created his own glue primer for cardboard so that the underpainting would

dry up quickly, and he could make an impasto, a thick top layer. This made it possible to finish field work faster

and was very important for transmitting a rapidly changing state of nature. Chursin always worked under a large umbrella,

which not only protected from rain and sun, but also helped to more accurately mix shades.

Upon arrival home from his travels, a "work review" was arranged for the family. Chursin could spend hours

talking about the beauty of the places he had captured and about the people with whom he had a chance to make

friends there, and there were many of them, thanks to his character.

Chursin's favorite artists were Michelangelo, Camille Corot, and Andrew Wyeth.”

Reproductions of Klim Chursin's works were often published in this journal and they were popular with the readers.

NEW COLLECTABLE ART – RUSSIAN REALIST AND IMPRESSIONIST PAINTINGS OF 20TH CENTURY

Russian Realist and Impressionist Art is a fairly new collectable art at the International Art market. The knowledge of most art collectors is confined to the Russian Icons and to the avant-garde experiments of the beginning of the 20th century. However, Russia brought the finest examples of the 19th century Realist & Impressionist art. This tradition was kept alive and continued in full in the 20th century. The realist art was devoid of any international art historian's attention as the official art of the Soviet State. Its charming beauty has been rediscovered in the last 15 year.

“Soviet Impressionist painting from 1932 to the 1970s was the best realist school of that period and perhaps of the entire century thanks to fine training and exceptional enthusiasm… This era might be called the “Golden Age of the Great Experiment”. (Dr. Vern Grosvenor Swanson)

Soviet art always favoured the sport theme. What was the role of games and entertainment in the society where all forms of human activity were supposed to have a particular goal?

Artistic aesthetics of sport representation were formed in the 1920s, the time when a harmoniously developed man became an equivalent to a patriot, same as in Ancient Greece. Examples of this connection could be seen in awards and lottery tickets of OSSOAVIAKhIM, Red Army and many other Soviet organisations. The key idea was a conquest of space and time, coupled with the task of preparing a physically developed man, who "is ready for labour and defence". A legendary badge GTO was created in 1930 when the sport theme was finally approved as an essential branch of Soviet Art.

Sport was portrayed not as entertainment but as one of the forms of labour activities of a Soviet man, an essential part of the preparation of a man for all difficulties. This heroic side as an integral part of Soviet sport was represented in women's and men's typical character portraits: a skier, a skater, a cyclist, a worker, a fisherman and so on. In one word - a Soviet man.

Young girls and boys portrayed on the paintings of that time were to cope with new challenges with the aid of sport. However, as it was in Soviet art the aims formulated by the Party and the ways they were executed differed vastly. In a series of graphic works by Tamara Rein the attention is brought to the beauty of a human body and there is very little of ideology and propaganda. In became obvious that Soviet art turned from avant-garde to its classical heritage.

At the turn of the fifties and sixties sport became a little less regulated and an element of play and freedom surfaced. Skiers on the painting by Vladimir Sakun "Spring on its Way" fascinate with their sincere happiness, in a same way as young people full of hope in Mai Danzig painting "On the Stadium". These images are not merely recognizable, we all have them in our family photo archives - this is not about sports any more, it is about new hope.

In the 1970s Nikolay Viting showed sport from a different angle. He brought the attention back to one of its essential qualities - sport as a spectacle. The entertaining aspect of sport in the USSR was a disputable territory between the government and the society. The audience didn't want to share the seriousness of the government's intentions, and therefore there was a fundamental mismatch and hidden resistance between the system, the athlete and the spectator.

Sporting events became as a magnetic power that brought out the repressed emotions of sportsmen and their fans. This sport magnetism is the main force of Viting's works. They enthral by their energy and mastery. Spectators watching a match got drawn into the world that is as powerful as the real one. Ansis Butnor's work "Fans" almost physically captures that transition into a different reality. The main focus of Soviet sports was not achieving body perfection of an individual or harmony of the mind and the body but making everyone fit the system. It wasn't easy to stand out from the crowd and form one's own individuality. Nowadays body once again became a private concern of a man himself. Young Latvian artist Ansis Butnors depicts these "new bodies" as rough simplified figures in the surroundings reminding mundane reality. The body increasingly abstracts from the natural landscapes of the Soviet period and even the social scenery of the post-Soviet era. New body occurs in the folds and gaps of the everyday, emerging in place of a vanishing Soviet background.

The Vladimir School of Art came into reality towards end of the 1950’s.

The 1950’s-1960’s was a meaningful time for the development of Russian art. The art format of this period was more expressive and individualistic and deviated significantly from the basic principles of socialist realism. The creation of the new style of art was already artistically imbedded. The style introduced by Nickolay Mokrov (1926-1996), together with three other artists from Vladimir, Kim Britov, Vladimir Yukin and Valery Kokurin became the trademark of the Vladimir School of landscape painting. Vladimir School artists involved the selection of traditional Russian scenery or landscapes as the central focus of their works. They transformed these traditional scenes through the use of new magical color schemes.

Instead of the impressionistic character exhibited by artists of the 1950’s, they worked in a new and explosive expressionistic style. Artists integrated into their works the full range and effects of colors including abrupt contrasts and dissonances. This special energy achieved through the use of colors, emphasized by the simplification of form, was similar to German Expressionism and French Fauve art. Soviet artists had ignored these artistic influences since the 1930’s. The artistic methods of Russian painters were close to those of postimpressionism.

However, the works had a significantly different form of expression. The artist’s paintings were less dramatic than those of European postimpressionists whose works had only a secondary influence upon artists of this era. Preponderant to the origin of this new style of Russian expression was the tradition of icon painting and folk art of Mstera and Gorokhovets. In spite of all innovations in Mokrov’s artworks the original prototype can never be transformed into pure abstraction. Using a small portion of realistic landscapes, Mokrov managed to capture the most subtle states of nature. Instead of the intrinsic ability of the sun to transform an ordinary scene into a plenitude of various hues and reflections, he took strong bright colors which, when splashed with light, became an artistic substitute for the sun -- a creative metaphor. Decorative flat compositions ignore any optical illusions.

The paintings are perceived by the viewer as if seen from a lower, horizontal perspective. First the plane, then the central focus of the composition divided by colors into a format of center, foreground and background, varied by colors but organized according to rhythm. Predominant color focal points are repeated. By increasing the level of the horizon, Mokrov makes the first plane of the painting seem closer to the viewer. All these elements existing in Mokrov’s art works are not only in accordance with decorative law but in accordance with his first impression and memory of the original landscape. Mokrov’s art ideas enriched not only the Vladimir school of landscape, but initiated a new form of development for the entire realistic tradition of Russian painting.

LENINGRAD SCHOOL OF ART

|